Amy Courts

Written Things:

sermons, songs, etceteras

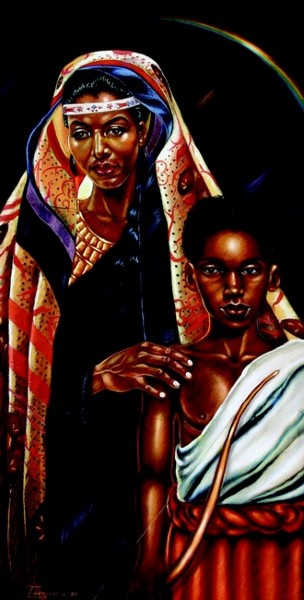

HAGAR: The First Prophet6/6/2022

Like many of us, I have often asked and been asked who of Scripture’s prophets is my personal favorite and why. I have at times joined the many giving preference to Jeremiah who reminds us that God knits us together in our mothers’ wombs, taking care with each cast, pull, and weave to create a uniquely beautiful work of art that warms, covers, and comforts (Jer. 1:5). Or Micah, whose recording of God’s most vital, fundamental instruction to us lays waste to all our idolatrous zeal and performative worship, reminding us that to love our Maker is to act: to love mercy and do justice and walk humbly next to God (Micah 6:6-8). And yet over time, through study and contemplation of what it means to prophesy, my favor has shifted to one not typically considered a prophet, but who nevertheless set the stage for all the prophets who would follow her. Before we dive in, we must establish how we understand and define “prophet” and “prophecy.” Literally, the Hebrew word נָבִ֥יא (nabi) simply means, “spokesperson” or “speaker.” Yet, given their unique voice in Scripture, we know a prophet of God is a particular kind of speaker set apart by what, to, and for whom they speak. The Hebrew nabi is not a future- or fortune-teller, nor do they offer magical predictions of threat or promise, except, perhaps, as future predictions converge with or stem from the present. Instead, and fundamentally, a prophet is one who speaks truth to power on behalf of the oppressed or marginalized. For many years, including throughout my undergraduate studies in biblical theology, I understood “speaking truth to power” as “speaking truth in a powerful way.” But what I now see with clarity is that prophecy is speaking truth to those who have power and challenging how they use it in relation to those without. It is rarely if ever “merely theological” but “by nature has political and social ramifications.” Prophecy always subverts the status quo and confronts those so comfortable with what is that they have no need to imagine what could be. Because a prophet’s work lay in turning the attention of dominant cultures and powers to the needs and concerns of the oppressed and marginalized, those who engage the Biblical prophets or modern-day prophecy must locate ourselves properly in the social, cultural, religious, and gender-sexual power structures that form and inform the world around us. Thus I make the case for a prophet who has not been widely, if ever, identified as such, but very much is one. She comes to us in the beginning of God’s story among the Hebrew people, and shows us what it means to disturb the powerful on behalf of the disempowered. Her story unfolds in Genesis 16 and 21. She is an Egyptian woman enslaved by a man of extraordinary wealth and power and by his wife. This wife is a woman to whom God will promise a literal nation of descendants numbering the stars, but whose lack of faith in that very same God, Their power, and Their promise compels her to first try and force God’s hand. (Gen. 18:1-15) Rather than seeing God’s promise as what womanist theologians call “making a way out of no way,” the wife sees only her own peril and limitations. All she sees is No Way. She is a barren woman in a world and culture where a woman’s worth is inextricably bound to her ability to bear children for her patriarch husband, and God’s promise seems no match for her lack. I, too, am a barren woman. I delivered my first and only child by emergency c-section. I nearly died of blood loss in the immediate aftermath, and was saved by an emergency hysterectomy that spared my life but stole my future. And so I identify with this woman. I feel in the now-empty spaces of my own body the ache, loss, and hopelessness she must have felt. Like her, I have laughed out loud when well-meaning Christians suggested that “anything is possible with God.” For while that may be true, humans do not spontaneously re-grow uteruses, and the absurdity of such an idea is comical. So, I get it: I get the feeling of un-woman-ness, un-becoming, and worthlessness apart from my ability to do the one thing that women are supposed to do. Barren women, infertile women, trans women, and all “othered” women who have been reduced and dismissed and erased due to our reproductive inabilities get it. Against our own lack, unbelief and distrust in a promise as ridiculous and impossible as the one given to the patriarch’s wife are utterly reasonable. Given her limitations due to barrenness, she does what many of us do when we lack the body parts but still retain some access to power. She uses her privileges of wealth and proximity to help ensure the preservation of her patriarch’s power. She sacrifices the body of her slave to the god of unfaith. Thus we meet the prophet Hagar. Hagar’s body is not her own. She is enslaved to Sarai, to be done with as Sarai pleases (Gen. 16:6). And what pleases Sarai, for now anyway, is to exploit Hagar’s body and womb for her personal family gain. Hagar the enslaved is given to Abram, raped by Abram, made pregnant by Abram, and forced to carry Abram’s seed for Sarai. Is it any wonder, then, that Genesis 16:4 describes Hagar as despising Sarai? And yet, Sarai still sees only herself as a victim, first of her barrenness and now of both her husband and her slave (vv. 5-6). Her abuse and mistreatment of Hagar escalate to such a degree that Hagar, an enslaved woman with nothing and no means, decides her only choice is to run away, pregnant and alone, into the wilderness. God finds and meets Hagar there in the wilderness. God calls her by her name and by her status -- for neither she nor how she suffers is invisible to the Lord -- and asks her what she is doing. And then, in a tragic twist during a short interaction, God sends her back to Sarai armed only with the promise God had also given to Abraham and would later give to Sarah as well: Hagar will survive this ordeal, and her descendants will ultimately be too numerous to count (vv. 7-10). In the meantime, she will be upheld and attended by God. On first glance, God’s command for Hagar to return to her abusive mistress appears cruel. But as womanist theologian Monica Coleman underscores in her book Making a Way out of No Way, God sends her back as a means of survival, which is “often inadequate in terms of full liberation, but…is one of the ways in which God saves.” In sending her back to Sarai, to enslavement, abuse, and the intolerable cruelty of a resentful woman with privilege and access to tools for revenge, God both ensures Hagar’s immediate survival and guarantees her and her son’s enduring legacy. For her unborn son, whom God instructed her to name Ishmael, meaning “the Lord has given heed to your affliction” (v. 11), would become a great nation and a living prophecy. In reply to what must have felt like another defeat, Hagar speaks truth directly to God by naming Them the God Who Sees (v. 13). The name she gives to God is profound for two reasons. Firstly, is the first time in the Biblical witness that God is given a personal name. And secondly, the name Hagar chooses does more than express gratitude for what has already been done: It commands future action, too. One who sees cannot unsee. One who sees cannot return to blindness or persist in denial of what has been revealed, lest They be a self-deceiving liar and hypocrite. Sight always transforms, always subverts, always commands action from the seer. This is how Hagar departs her wilderness encounter and returns to Sarai: with God’s promise of survival, as well as her own creatively-rendered expectations of the Divine. She has spoken truth to the only power to whom she has access -- that is, to God’s self -- and has gone forward in faith that the God who sees will act. Hagar’s story is quiet until Genesis 21. She gives birth. She and her child remain in Abraham and Sarah’s home until Sarah has finally given birth to her own son, Isaac, and no longer has need or want of Hagar or her “ass” of a son, Ishmael (vv. 8-10). With her own promised future intact and growing, Sarah sees the two of them only as a threat to her privilege, access, and power, and to Isaac’s inheritance (v. 10). So she compels Abraham to banish them to the wilderness to die for a second time (v.14). There in the wilderness of Beer-sheba, once again alone, hungry, out of water and ways, and feeling certain of her and her promised son’s impending deaths, Hagar lifts up her voice and weeps before God (vv. 15-16). This, too, is a prophetic wail of truth to power, a cry for The God Who Sees to see her again, and God does. When Hagar -- a slave, a nobody whose body had been used, whose blood had been spilled, and who with her son had now twice been sacrificed to the wilderness -- screams her truth to Power, it is a mother’s groan (v. 16b). The kind too deep for words. The kind the Spirit joins with in intercession before God. And God hears her crying son, whose very name and being command God’s ears. God comes to her as God did before, once again naming her, and her troubles and fears (v.17). God reaffirms Their promise that Ishmael would live. And God opens Hagar’s eyes to a well in the wilderness, giving them both hope for the future and water for right now. All else we know of Hagar is that she and her son both lived. Ishamel thrived in the wilderness under God’s direct care and married (vv.20-21). For, God spent Their power to deliver on the promise They made when Hagar first escaped enslavement and demanded a way out of no way. Hagar’s story may be relatively small within the grand narrative of Scripture, but it is profoundly instructive for today. A slave girl is the first to name God, and to be seen, heard, saved, and liberated into healing, wholeness, and legacy. She is the foremother whose liberation would be echoed in Israel’s from Egypt, and in ours from sin and oppression. She is a nobody whose progeny, the son of a slave and a child of sexual violence, became a wild ass of a man and a living prophecy. To Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Israel, and all God’s people, Ishmael was a breathing, enfleshed reminder that whenever we trust the lies of patriarchy, power, and supremacy over and against the promises of God, persistent and heated conflict will follow for and through many generations. Whenever we engage the prophets in search of the messages they bring to God’s people both then and now, we must locate ourselves properly within the story. Writing as a white cisgender seminarian of the overwhelmingly white Evangelical Lutheran Church of America to others like myself, it can be certain that I am not Hagar. Indeed, despite that my bisexuality and queerness make me vulnerable to violence in some ways similar to her, both my whiteness and lifelong proximity to white christian patriarchy and white supremacy make me a beneficiary thereof. I am much more like Sarai/Sarah. I, like Sarah, am a woman who has been abused, reduced, dismissed, and exploited by patriarchy. Remember, Sarah was twice trafficked by her own husband to powerful men, once before and again after she trafficked her slave to him. She was a beautiful woman who, on account of her sex and gender, was seen first as a threat to and then as a tool for her husband’s own gain. Before she ever gave Hagar over to be sexually assaulted by Abram, she was given by him “as a wife” to Pharoah. Like her, I have been both victim of patriarchal and sexual violence, and I have overseen or defended it against other women. Like Sarai, and like so many other white Christian straight-passing women, despite being threatened or assaulted for our gender or sex, I have at times weaponized my privileges of race, femininity, and passing-straightness in order to make gains for myself within patriarchal and racial hierarchies. Like Sarai, I am a woman who dwells too often in her perceived lack. I am naturally inclined to use what privilege I do have to exploit those with less, rather than lending the full weight of my privilege and the lessons of my experience to move in solidarity and mutuality with my marginalized siblings in order to undo those hierarchies and build a Beloved Community rooted in justice, liberation, and collaborative power. I am more likely to see women like me occupying spaces of power in the bishopric of the ELCA and to believe our ascension to top of the religious hierarchy is a sign of its defeat than I am to stand in solidarity with my Black, Brown, Indigenous, and Queer siblings who are calling for utter transformation of our Church through the subversion and dismantling of hierarchies that have evolved to make space for me but not for them. I am more likely, as Susanne Scholz writes, to “let [patriarchy] off the hook” by turning against my sisters than I am to work with them to destroy the hierarchies that make us each other’s enemies while the system in which we all suffer grows. And so, given my own predispositions within a nation, church, and synod which offer paternalistic welcome and protection to white women, and which permit our assent but only within the bounds of expected assimilation to the patterns of our male forebears, it is incumbent upon us to resist the lure of these prestigious offices and instead imitate God by going to find and see Hagar in the wilderness. We must seek out and listen to the voices of Black, Indigenous, Immigrant, Queer, Non-Binary, and Women of Color. As legislative efforts to subjugate Black bodies, women’s bodies, Trans bodies, and Queer bodies to white churchian cis-hetero male authority steadily rise to record numbers, we are without excuse. We must determine to see ourselves as we really are rather than as we have been conditioned to believe we are. Only then will we see that Hagar has been among us all along. She speaks truth to power with unflinching courage and honesty, calling on God to see and sustain her and her children and provide water for each moment in the desert, and calling on those of us with or in proximity to power to realign ourselves. We can aspire to positions of power and believe the lie that once we arrive we will handle the power differently. Or we can receive to Renita Weems’ invitation to siblinghood and mutual struggle against the structures of patriarchy and supremacy that pit us against one another, and instead work to extend and transform privilege for the benefit of the least of these. Specifically, we can see Hagar and heed her voice when our Black, Brown, Indigenous, and Immigrant siblings talk about how affectionately they were pursued by our seminaries, which are desperate for students from “diverse” backgrounds, only to be repeatedly silenced, dismissed, and marginalized for daring to show up among colleagues in their full, unapologetic Brownness and Blackness. We can see Hagar and heed her voice among our LGBTQIA2S+ colleagues who are courted by our churches and seminaries, and promised inclusion and affirmation under rainbow banners, only to face persistent and pervasive homophobia in the classroom and pews, which goes on unchallenged by professors, pastors, and synodical leadership. We can see Hagar and heed her voice among our rostered colleagues who are in one season praised for writing love letters to our white denomination, and in the next chastised for calling us to costly action through reparations. We can see Hagar and heed her voice in the cries of our North Minneapolis neighbors desperate for liberation from our simultaneously over- and under-policed streets, when their Black sons are targeted for arrest on suspicion of manufactured crimes, but where known loci of violent crime remain unattended and ignored by our police precinct. We can see Hagar and heed her voice in the witness of Black whistleblowers and refugee women whose bodies have been robbed and mutilated at ICE internment camps, and whose children have been trafficked all across our country as foster children and adoptees to good [white] christian families, with little hope of reunification. We can see Hagar and heed her voice in our Indigenous siblings and elders who are still here, still dancing, still drumming, and still protecting the earth and its water. They are still honoring the sacred against all odds, and despite the genocide begun centuries ago by European Christian colonists who sought to “kill the Indian to save the man,” which in so many ways continues to this day through attacks upon and erosion of Native sovereignty and treaties. And I can feel and heed the voice of Hagar heavy on my own chest, clawing at my own throat, ringing in my own ears, burning my own eyes, and boiling in my own blood, as her Black sons cry out for their mamas from the streets on which they die under the heavy, unmoving knees of white Christian supremacy. Like Hagar and Ishmael’s, the Black and Brown bodies of kids like Tamir Rice, graduates like Michael Brown, fathers like George Floyd and Philando Castile, daughters like Breonna Taylor, aunts like Atatiana Jefferson, and all the unnamed, long-erased Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women are enfleshed, apocalyptic prophecies that show and tell us both who God is -- the One who sees and hears, who helps and gives legacy to the afflicted -- and who we are. Today, as then, our minoritized siblings live and die at odds, sometimes necessarily riotous odds, with our entrenched power structures. And they invite us, as the Rev. Dr. Wilda Gafney says, to resist “the temptation to exercise whatever privilege we have over someone else” and choose instead to “stand with them in shared peril” and be transformed. In considering Hagar’s prophetic Naming of God and her son’s prophetic enfleshment of God’s option for and alignment with the afflicted, the question for me is and remains: Where and with whom will I align myself, as a member of both dominant and dominated cultures; as a beneficiary of many privileges according to my class and race, but simultaneously dehumanized and fetishized according to my sex, sexuality, gender? Tori Douglass, an anti-racism educator and the creator of White Homework, teaches that “You cannot renounce your privilege. You can only spend it.” And so that is the final and ongoing challenge I submit to all of us who meet Hagar, a prophet of and to God, in the wilderness of Genesis 16 and 21: Will we, like Abram and Sarai, spend our privilege on acquisition and assimilation to power, and so perpetuate systems and cycles of oppression? Or will those of us with access to power commit to the practice of imitating God by finding, hearing, and heeding Hagar’s and Ishmael’s prophetic cries, and using our privilege to see and empower the afflicted? Like Hagar and Sarai, Isaac and Ishmael, we will die at odds with someone. The question is only, with whom? Will we stand at odds with our siblings who’ve been raped, pillaged, displaced, enslaved, lynched, and who still rise? Or will we stand in solidarity against the powers over which we all stand a chance only if we stand together? BIBLIOGRAPHY Alvarez, Priscilla. “ICE Whistelblower Alleges High Rate of Hysterectomies and Medical Neglect at Georgia Facility.” CNN Politics, September 16, 2020. Backhouse, Stephen. “Truth to Power: What could the prophets of old reveal about today’s truth-tellers and false prophets?” Plough, February 17, 2022. Bruggemann, Walter. The Prophetic Imagination, second ed. St. Paul: Augsburg Fortress, 2001. iBooks. Coleman, Monica A. Making a Way Out of No Way: A Womanist Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2008. Douglass, Tori Williams, producer & creator. White Homework. Season 1, episode 9, “Is White Privilege Even a Thing?” Aired July 30, 2020. Apple Podcasts. Duncan, Lenny. “Why the ELCA Needs to Start a Reparations Process, Part 1.” A Sorcerer’s Notebook (blog), September 15, 2020. Filipovic, Jill. “Adoption of Separated Migrant Kids Shows ‘Pro-Life’ Groups’ Disrespect for Maternity.” The Guardian, October 30, 2019. Gafney, Wilda C. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017. Greene, Peter. “Teacher Anti-CRT Bills Coast to Coast: A State By State Guide.” Forbes, February 16, 2022. Lavietes, Matt and Elliott Ramos. “Nearly 240 anti-LGBTQ bills filed in 2022 so far, most of them targeting trans people.” NBC News. March 20, 2022. Lipka, Michael, “The Most and Least Racially Diverse Religious Groups in the U.S.” The Pew Research Center, July 27, 2015. Nash, Elizabeth, Lauren Cross, and Joerg Dreweke. “2022 State Legislative Sessions: Abortion Bans and Restrictions on Medication Abortions Dominate.” Guttmacher Institute, March 16, 2022. Rosario, Isabella. “Jesus Was Divisive: A Black Pastor’s Message to White Christians.” NPR CodeSwitch, June 12, 2020. Rosenberg, Joel W., Ph. D. “Genesis.” In The HarperCollins Study Bible: New Revised Standard Version, edited by Wayne A. Meeks, 3-76. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993. Sadeghi, McKenzie. “Native American leader says tribal sovereignty still threatened from ‘every corner’.” Salt Lake Tribune, February 11, 2020. Scholz, Susanne. Sacred Witness: Rape in the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010. Strong, James. The New Strong's Expanded Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010. BibleHub.com. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://biblehub.com/hebrew/5030.htm. https://biblehub.com/hebrew/3458.htm. Weems, Renita J. Just a Sister Away: Understanding the Timeless Connection Between Women of Today and Women in the Bible. New York: Warner Books, 2005. iBooks. “How George Floyd Died, and What Happened Next.” The New York Times, November 1, 2021. “Keeping History: Plains Indian Ledger Drawings | “Kill the Indian and Save the Man.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Nov. 13, 2009-Jan.30, 2010.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply.AMY COURTSSermons + Songs + Poems Archives

June 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed