Amy Courts

Written Things:

sermons, songs, etceteras

|

This sermon was originally preached on June 19, 2022 at Oak Grove Lutheran Church in Richfield, MN. The service may be viewed here. Second Sunday after Pentecost Lectionary Texts: Isaiah 65:1-9 | Galatians 3:23-29 Gospel Text (included below sermon ): Luke 8:26-39 Oh Great God, Mothering Spirit, Liberator and Life-giver, greet us this morning with fresh ears and open eyes that we may love each other well. Amen.

In October 2009, after a few years of touring as a solo artist in nashville and partnering with a non profit doing humanitarian work throughout Africa, I traveled to Gulu Uganda with a group of 9 other artists where we painted murals at an orphanage and school, and met with about 100 women living openly with an ostracizing HIV positive status. While there, we also had the opportunity to attend a local church in a small village on the outskirts of Gulu proper. That Sunday’s worship was an incredible, spirit-filled service that lasted 4 hours but truly only felt like one, if you can believe it. The service was fluid and seamless, and it was easy to feel connected to Spirit and everyone gathered. But there was one man in particular who captured our attention because at various points in the service, he fell to the ground in convulsions. I say “fell,” but that doesn’t quite describe the force with which he hit the dirt of this large straw-covered church: It was more like he was thrown to the ground, except that, to our eyes, it was just him, violently falling and then rising uninjured. We were told this was common for him; that his demons were known and had been confronted many times, and that his pastors and community were working on his exorcism -- it was just taking some time. But they told us not to worry; it was all well under control. Some of us were shocked to hear them speak so freely and confidently not only about this demon possession, but about their own efforts to keep on casting them out, week after week, while fearlessly welcoming him into the presence of God. And as we thought about and discussed the whole thing throughout the rest of that day, we realized something profound, which altogether transformed what we'd witnessed. I know it will sound wild, and trust me when I say we went over and over it. But I n the end we all agreed to what our collective experience and memory confirmed: It was at the name of Jesus Christ that this beloved man fell, every time.

0 Comments

The following essay was written for and submitted to the faculty of Luther Seminary for consideration for the The G.M. and Minnie Bruce Prize in New Testament . While my submission was not chosen to receive the award, I remain proud of the research and work I've done to write and present this paper on The Parable of the Good Samaritan in conversation with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr and Deitrich Bonhoeffer. My hope is for some of the insights I gained through the study and writing may be as transformative for you as they have been for me. The full footnotes and bibliography are available on Scribd. (c) 2022 Amy Courts Koopman Luke 10:29-37 (NRSV) But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” Jesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, ‘Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.’ Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?” He said, “The one who showed him mercy.” Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.” Introduction

The parable of The Good Samaritan stands throughout Christian history as one of the most compelling and convicting of Jesus’s ethical instructions to those who would claim to be his disciples. We are often like the famed lawyer in the story, inclined to reduce the definition of “neighbor” to ever-smaller meanings that ultimately require nothing of us. It is a story not primarily about a desperate man dying in the road, but about how those who might otherwise define themselves as fine upstanding faith leaders are forced to reckon with what the apostle James called a dead faith (James 2:14) when compared to the universally and dangerously altruistic compassion demonstrated here by “enemies.” Among modern white American Christians for whom Christianity has become more an exclusive club of insiders than an expansive community of God’s beloved, and who desperately need a whole-person (heart, soul, mind, body) revival to draw us to acts of justice and mercy especially when such discipleship is costly, this story takes on profound importance. The Good Samaritan commands modern readers’ attention to both the systemic injustices that create “bloody ways” for our neighbors, and to the personal excuses that keep us from living our faith in risky, neighbor-loving ways. For those of us living at social locations of privilege and power, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s commentary speaks directly to our predicament: Most of us, when challenged to neighborly action, will naturally ask, “what will happen to me if I help this man?” But Jesus’s parable in Luke 10 declares that a good neighbor always reverses the question and instead asks, “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” In so doing, Jesus transforms the conversation from one of theological acrobatics performed by legal experts into a one about “concrete expression[s] of compassion on a dangerous road.” In doing so, Jesus makes concrete, whole-person demands of all who would claim to love God and be Christ’s disciples. HAGAR: The First Prophet6/6/2022

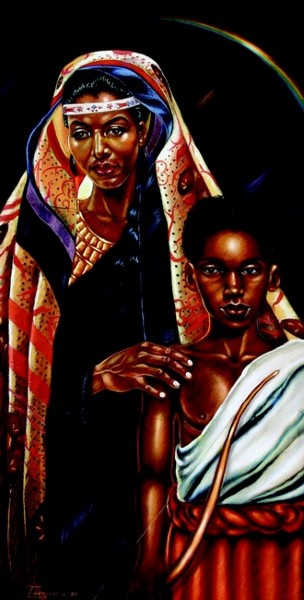

Like many of us, I have often asked and been asked who of Scripture’s prophets is my personal favorite and why. I have at times joined the many giving preference to Jeremiah who reminds us that God knits us together in our mothers’ wombs, taking care with each cast, pull, and weave to create a uniquely beautiful work of art that warms, covers, and comforts (Jer. 1:5). Or Micah, whose recording of God’s most vital, fundamental instruction to us lays waste to all our idolatrous zeal and performative worship, reminding us that to love our Maker is to act: to love mercy and do justice and walk humbly next to God (Micah 6:6-8). And yet over time, through study and contemplation of what it means to prophesy, my favor has shifted to one not typically considered a prophet, but who nevertheless set the stage for all the prophets who would follow her.

Before we dive in, we must establish how we understand and define “prophet” and “prophecy.” Literally, the Hebrew word נָבִ֥יא (nabi) simply means, “spokesperson” or “speaker.” Yet, given their unique voice in Scripture, we know a prophet of God is a particular kind of speaker set apart by what, to, and for whom they speak. The Hebrew nabi is not a future- or fortune-teller, nor do they offer magical predictions of threat or promise, except, perhaps, as future predictions converge with or stem from the present. Instead, and fundamentally, a prophet is one who speaks truth to power on behalf of the oppressed or marginalized. For many years, including throughout my undergraduate studies in biblical theology, I understood “speaking truth to power” as “speaking truth in a powerful way.” But what I now see with clarity is that prophecy is speaking truth to those who have power and challenging how they use it in relation to those without. It is rarely if ever “merely theological” but “by nature has political and social ramifications.” Prophecy always subverts the status quo and confronts those so comfortable with what is that they have no need to imagine what could be. Because a prophet’s work lay in turning the attention of dominant cultures and powers to the needs and concerns of the oppressed and marginalized, those who engage the Biblical prophets or modern-day prophecy must locate ourselves properly in the social, cultural, religious, and gender-sexual power structures that form and inform the world around us. Thus I make the case for a prophet who has not been widely, if ever, identified as such, but very much is one. She comes to us in the beginning of God’s story among the Hebrew people, and shows us what it means to disturb the powerful on behalf of the disempowered. AMY COURTSSermons + Songs + Poems Archives

June 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed