Amy Courts

Written Things:

sermons, songs, etceteras

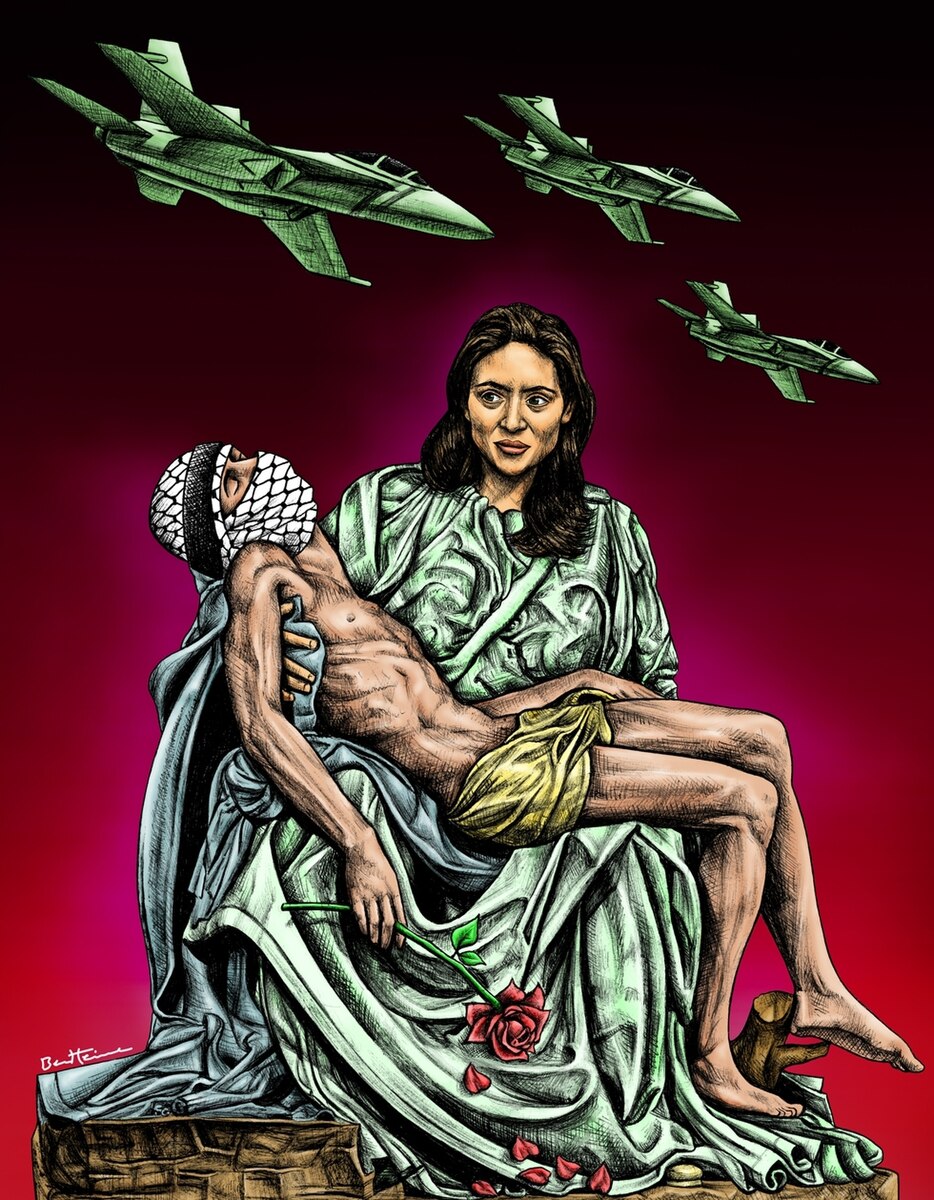

Good morning, beloved of God. Today we enter into Holy Week, into the final few days of Jesus’s life. As I read this familiar story again this year, I was drawn to the ways in which it begins and ends with the presence of Christ’s closest friends. Throughout this recounting of Jesus’s last days, hours, meals, and moments, I can't help but notice the real people who showed up in fearful and risky, costly, and cowardly ways. And so As I think about this story and all the ways it invites us to witness grief, the first thing I am conscious of is our culture’s general aversion to the process of grieving, mourning, wailing, and witnessing -- especially publicly. We tend to be stoic people, uncomfortable with grief and intolerable of the quiet, steadfast presence mourning requires. So when we are grieving, we offer apologies for feeling like a burden, and when our friends grieve, we offer platitudes, like “everything happens for a reason,” and “God never gives us more than we can handle” (which are both garbage by the way). We do not like, nor do we understand the purpose and power of grief, so we often interrupt it and speed it along. We rush through the passion to the Resurrection, skipping some of the most important and transfigurative moments along the way. And so today, I am inviting us to do the opposite, and to do it together. In her book Untamed, Glennon Doyle writes this of the period following her sister’s divorce: “One evening, I followed her downstairs and stood outside her door. As I prepared to knock, I heard her crying softly. That is when I realized that where she was, I could not go. Grief is a lonely basement guest room. No one, not even your sister, can join you there. So I sat down on the floor with my back against her bedroom door. I used all I had, my body and my presence, to hold vigil, to guard her process, to place myself between her and anything else that might disturb or hurt her. I stayed there for hours. I came back to her door for that nightly vigil for a very long time.” She says that after a year of vigil, her sister re-emerged, a whole new person; that “It’s like that small, dark room was a cocoon. All that time she was in there undergoing a complete metamorphosis. Grief is a cocoon from which we emerge new.” (Doyle, 270-271) The Jewish People understood this. They did not barge into that basement to drag a mourner back up to the sun. Instead, Jesus and his contemporaries were raised with “very specific [instructions] for communal mourning -- like the loud public expressions of sorrow and lamentation, the wearing of sackcloth mourning clothes made of rough goat-hair fabric, and committing, as entire community, to a full 30 days of intentional collective mourning. They understood what Glennon named: that entering into grief and staying present with the grieving in their cocoons, created its own kind of community cocoon, from which all of them, together, would re-emerge as totally transformed people, as a totally transformed people. And I know this because we would not be here today, part of a global community of people more than 2000 years later, still rooted in Jesus Christ, if not for those who stayed and bore witness to his execution. Their witness transformed a small band of believers into an imperial menace whose faith and apostleship spread so powerfully across the region that it ultimately aided in the collapse of Rome, having "displaced the polytheistic Roman religion, [and its “divine” emperor] and shifted religious focus away from the glory of the state and onto a sole deity, Jesus Christ, whose kindom was utterly different." And so let’s meet some of these witnesses, one by one, and learn from them what it means to be present in and transformed by deep deep pain. We enter into the story at the house of Simon the leper, in Mark 14:3, where a woman of pretty extraordinary Boldness comes to Jesus with a ridiculously expensive bottle of nard -- a fragrant perfume which, by the way, is mentioned only one other time in Scripture, and that is in the Song of Songs -- and, in a radical act of intimacy and love, pours it over his head and into his hair. Elsewhere in the gospels, she is said to have washed his feet with the perfume, which is significant because the next time we see such an intimate and humbling act, it is Jesus washing the feet of his disciples. So while I’m not suggesting anything scandalous, the closeness of this pair -- Jesus and the woman with the nard -- must not be missed. Neither do I want us to start this journey without naming the profound presence of women in Jesus’s life and ministry, such that her act of worship was followed directly - and in kind - by Jesus’ kingly act of service at the Last Supper, where he poured out his whole self. It’s okay if it’s awkward and weird for you to imagine all of this. I just want you to sit with the closeness and intimacy of Jesus’s relationship to this core group of disciples, including the women. Because now we go to Gethsemane. A frustrated and terrified Jesus is wailing to his father, sweating blood, and his best friends cannot even stay awake for him. Ponder how defeated and alone Jesus already felt, knowing what was to come and that they could not and would not be able to handle it. Knowing that at any moment now, their lives were going to be totally upended. And imagine with me that moment, when the Roman Police showed up, the disciples are jolted from their sleep, surrounded by armed and deadly agents of Empire. What is happening in their bodies and minds? Look at Peter, whose fight response is triggered and who immediately goes into battle mode, cutting off one of their ears. Imagine how Jesus’s reprimand crashes in his body, telling him to put away the sword, because it is the weapon of Caesar’s Empire, not his. Notice also how, in Mark 14:48, Jesus names for his disciples and these Roman agents precisely what they are up to. He knows the Empire is here for him, and he needs his disciples to understand the gravity of the shift now taking place in the universe: That his earlier warnings about his heading for death are happening now, and they are up against the unstoppable wheel of Empire. Consider their confusion… the rage and fear and utter helplessness they must have felt against such untouchable powers, the shame of not understanding until this moment what Jesus had been trying to show them for years. Think of the urgency of their need to do something and the overwhelm of having no clue what that something is, never mind how to get away with it. Ponder, next, how it felt for Peter, a few hours later, to be publicly identified as a disciple of “the Nazarene” who had just been condemned by the High Priests -- themselves, you may recall from Wednesdays inside the text -- moving in ways so as not to trouble the fragile Roman Peace but maintain their tenuous autonomy as a religious people under violent occupation. Peter’s closest friend is about to be sacrificed to Rome as a tax for peace, and tortured by an empire whose methods, he’s well aware, are extreme, obscene, and horrific. Friends, there was a time when I despised Peter for his cowardice -- for his proclamation at the last supper that he would never ever deny Christ only to do just that, and three times over, mere hours later. But as I look at this scene now, with my holy imagination, I think I get it. I feel his fear. His terror. His helplessness. And I cannot say in full honesty I would have done differently. Self-preservation is not a choice, it is innate. And Peter hadn’t yet developed any sustainable practices of resistance to carry him through this moment. He would, in the years to come. In fact, he is so transformed by what’s to come that when he is executed by that same empire, he goes willingly, asking only to be crucified upside down, saying he did not deserve the honor of being killed like Christ. That man was no coward. And the crowds? Whew. Just days ago they lauded Christ, singing Hosanna Hosanna at his triumphal entry, which itself could be seen, according to Gary Alan Taylor, as “a political protest, a kind of counter-demonstration mocking the ways and means of [an] empire [that was] ordered by nationalistic power, racial privilege, colonial subjugation, and economic exploitation.” “It was an anti-war, anti-imperial demonstration [led by] Jesus’ [whose] vision is a world turned upside down and ordered by reciprocity, love, freedom from bondage, radical inclusion, and human equality.” And yet -- now -- these crowds cry for his crucifixion. Folks, I don’t think it’s because they are bad or evil or in any way substantially different from you or me, but because they are not rooted in The Way, and so are easily persuaded back to a safer, more comfortable and familiar status quo. We don’t really have to imagine this rapid shift in cultural climate, because we’ve seen it again and again in our own time. Like after George Floyd’s murder -- That atrocity sparked outrage - until the outrage took an uncomfortable form of protest against the status quo, at which point outrage gave way to resigned acceptance. “The way things are” is easier to accept than the way things could be, especially when change demands disruption. And that can be scary. And now - notice The women. They are all who’s left. Though certainly crippled by fear and wasted by grief, they stay. They watch Jesus nailed to and raised on the cross, and they stay. They bear witness with him and for him, keeping their eyes trained on the obscene horrors before them, so that, if nothing else, he will not be alone through his *hours* of suffering and dying. These are Glennon Doyle’s kind of women: the kind of sisters who hold that space and guard it with ferocity, committing their bodies to the vigil of his death, through the piercing of his side. To his lowering from the cross. To his burial in the tomb. They stay. Ponder for a breath how brutal the cost was, physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually to remain present with Jesus at death’s door and to witness him walk through it. There can be no doubt those women emerged from the dark cocoon of that day utterly transformed. When I think of these women, do you know who I see? I see Harriet Tubman who escaped enslavement and who, despite experiencing and witnessing atrocity after atrocity on the underground railroad to freedom, kept coming back for more, no matter who gave chase. I see Mamie Till who insisted on an open casket at her precious son Emmet Till’s funeral, so that all who came could bear witness to the disfiguring violence of whiteness in Jim Crow south. I see Deitrich Bonhoeffer, who, as Pastor John reminded us Wednesday, accepted his Christian responsibility to confront the Nazi regime. Who gave his body to the overthrow of Hilter’s empire. Who spent his last days in prison preaching the healing and liberation of Christ, and went to his death, having no doubt whose empire he served, proclaiming “This is the end, but for me it is the beginning of life.” I see the survivors of the October 7th attacks in Israel, and the families of those still held hostage, begging and pleading for the safe return of all who were taken. And every day I see our siblings in Gaza. The men and boys with hands and backs broken from months of digging through rubble to pull survivors out from under. Grandmothers showing us their crushed and dismembered grandchildren. Mothers wailing over their starving infants who were born into genocide and probably will not live to see its end. All of them begging us see those who are right now being sacrificed to Empire, just like Jesus was, and asking us to Not. Look. Away. If the Passion commands anything, it is that we do not look away, do not look away, Stay and do not look away. There is so much grief in this world. Pain, like the poor, will always be near, war will always be at our doorstep, the broken will always yearn for witnesses who will not only keep vigil at their basement door, guarding their grief, but who will also hold fast and near, in solidarity with them to the very end. The fact is, folks, we are always in solidarity with something. We can draw near to Empire, hoping it will protect us if we do, which is often the easiest and most comfortable choice to make. But today I am asking us to be like the women who stayed. To draw close to the oppressed. To bear witness to their trauma and keep vigil when they’re in the throes. I am inviting us to cultivate practices together that will strengthen our staying muscles, and empower us to not grow weary in doing good, and to not look away from those crucified among us. And in the same way, I’m asking us to cultivate practices of radical joy and rest that will nurture and increase our mutual love in Christ Jesus, which will in turn increase our capacity to watch, bear witness, and stay in solidarity, just as the womens’ closeness to Jesus before his death kept them near the cross when everyone had scattered. In closing, I offer this: A song that spilled out in all of an hour as I pondered all these things at the piano. We will dim the lights as best we can, and If you feel comfortable doing so, I invite you to close your eyes and receive these blessings. "Blessed Are You" (c) 2024 Amy Courts Music

Blessed are you who remained Bore witness and did not look away Holy Spirit come intercede and pray For all the ones who remained Blessed are you who stayed Near to the promised one, unashamed Holy Spirit comfort and ease your pain Blessed are you who stayed Oh Blessed are you who stayed Blessed are you who attend Keep vigil unto a bitter end Holy Spirit, come with Her medicine Healing the hearts of the friends Who kept watch until the end Blessed are you who return Those whose betrayal the Spirit turns From a binding grief to a call that burns Warming the ones who return Blessing the ones who have heard Blessed are you

0 Comments

Leave a Reply.AMY COURTSSermons + Songs + Poems Archives

June 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed